The Texas Rangers are almost certain to shut down Yu Darvish for the season, because that’s what a smart team would do, and the Rangers are no dummies. They don’t cater to the whims of a manager who after all these years doesn’t care to acquaint himself with the intricacies of arm injuries, and they don’t kowtow to media members looking for some bright light in this Alaska winter of a season, and they certainly don’t put at risk one of the most valuable assets in baseball to salvage some sliver of a year long ago lost.

The fact that this is even an issue in 2014 – in a year that has seen pitcher after young, dynamic pitcher wake up from an anesthetic slumber with a scar on his elbow – speaks to the willful ignorance that still pervades certain factions of baseball. Earlier in the month, Darvish’s right elbow hurt. An MRI showed inflammation, which was about the best-case scenario. The Rangers should celebrate the fact that one of baseball’s five best pitchers isn’t so myopic to think he alone can solve the woes of an injury-destroyed team that owns the game’s worst record at 52-80. Pride has killed too many arms to count.

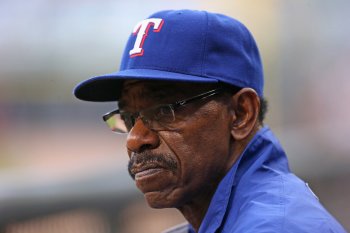

And yet it’s still one of the prevailing currencies in baseball – in sports, really – and somehow gets conflated with wanting to win. Take Rangers manager Ron Washington, a man whose candidness is one of his greatest qualities but, on occasion, exposes his weaknesses. At one point, he lamented Darvish’s slow recovery time, saying: “So he’s got inflammation. I’ve got inflammation.”

It got a chuckle, Wash being Wash, and he later apologized for it in a radio interview with 103.3 FM in Dallas. During that same interview, of course, Washington said he wanted Darvish to come back so “he doesn’t quit on his teammates; that’s all there is to me.” And then he suggested what Darvish felt in his arm differed from the diagnosis. And the entire thing spiraled down a wormhole of ignorance to a fetid place where dogmatism and machismo foster every last bit of this nonsense.

Yu Darvish came to the United States from Japan, where he was one of the most famous people in the country and the most well-paid athlete, because he craved the competition of Major League Baseball. He threw away the safe to embrace the uncertain because he wanted to be the best in the world. To suggest that because he doesn’t want to pitch through an injury makes him a quitter is wrong on every level, from factual to human and each in between.

Ron Washington, it should be said, is considered a players’ manager. Yu Darvish, it should be noted, is the Texas Rangers’ best player. Washington’s frustration over a season’s worth of injuries – a decade’s worth, frankly, with the Rangers now sporting nearly $71 million worth of players on their disabled list – spilled over into the wrong forum, with the wrong scapegoat, and that’s not the sort of look any manager leading his franchise to the No. 1 pick in the draft needs.

Were Washington inclined to ask, he might learn that one of the greatest causes of catastrophic arm injuries is returning too quickly from lesser ones. Even the slightest tweak of mechanics to make up for the most minute pain can cause a pitcher’s rhythm to fall apart, which forces more adjustments, which leads to undue stress on the elbow or shoulder.

More and more organizations are adopting the slower-is-better method with rehabbing pitchers, particularly in light of Daniel Hudson and Jarrod Parker and Kris Medlen and Brandon Beachy’s elbows necessitating a second Tommy John surgery. The Diamondbacks are taking particular care with Patrick Corbin, their young ace. While Hudson returned from his first surgery just after the 11th month, Corbin’s timetable is between a year and 14 months. Baseball always seems one step behind the arm. This is another effort to at least even the score.

And so even as sources say Darvish’s elbow has improved, and were this a different circumstance he probably would pitch, it’s important to understand this is not a different circumstance. He would need to build up arm strength, pitch a simulated game in Arizona and maybe, just maybe, make it back at the end of September for a start or two. The Rangers aren’t going to tempt Darvish’s elbow, not with the rotten team they field on a nightly basis, not with him making it past his 28th birthday sans a scar on his arm, not with his contract running through 2017.

Washington is a competitor, so he believes all the games – the ones in the World Series he has managed and the ones on a team whose season may well have ended months ago – should be treated equally. That when you spend 162 games and eight months with a group of guys, you owe it to them to grit out injuries. Cases certainly exist where that’s true.

Not with the arm. Ever. And barring an about-face from Darvish, he won’t be the latest to allow his pride to interfere with his franchise’s – and his – future. He doesn’t owe anybody. Not Ron Washington. Not Adrian Beltre. Not Jon Daniels. Not the fans. Not the Texas Rangers. No one. Darvish gives the Rangers what his body allows, and considering the muscle he has packed on since coming to the U.S., he desperately wants for it to allow as much as possible. So far, a 3.27 ERA and 11.2 strikeouts per nine innings over his first three seasons seem like a pretty fair return.

Injuries are part of every sport, and if Darvish’s continue, his reckoning will come via the free-agent market. In the meantime, Washington ought to change his narrative, lest he isolate those most important to him, and his mouthpieces should do some research. This isn’t about pride. It’s not about quitting, either. It’s about being smart. They could stand to learn a thing or two from Darvish.

More MLB coverage from Yahoo Sports:

- Sports & Recreation

- Baseball

- Yu Darvish

- Ron Washington